Everything is Onions

Here I have cobbled together a series of audionotes I kept

along the way, in the long stretches when I was alone between the fields. If I

did encounter people on the walk, it honestly felt as though someone was

intruding on my solitude – especially when I was trying to record a voice note

in self-conscious stream-of-consciousness. The sound of other voices, however

playful, left me cold, dejected. I felt more alone in the moments when I

realised I wasn’t.

I haven’t made a point of mentioning the walk anecdotally

since I undertook it, mostly because I only got one tangible thing out of it – a particularly lovely red onion, plucked from the ends of a

field already well-ploughed; it’s not stealing if the tractor turns it down. A second later the tractor came round again and I ran away. I was running on broken

soles, boots decomposing at the 27th mile. I would have eaten

the onion raw if I hadn’t been waiting for the first pub in Orford: the Jolly

Sailors, now forever marked for me as where I finished walking in a county that - beyond W.G. Sebald, the family of George Orwell and perhaps Ed Sheeran - is more

or less unknown.

This walk would be punctuated by unknowns, the opposite, in fact, of the usual walk to a country pub, and even less of a commute. But I never saw the unknown as the main difference; to my mind, journeys differ not in how much we know them but in how we consume them. On Netflix, they had been releasing camera footage from the front of a train as it travelled across the beautiful forests and fjords of Norway. It was a breakout hit of mindfulness and chill-out. I imagined there wouldn’t be much demand by comparison for watching a film slowly play of someone walking through field after field in long-eroded East Anglia. Such a programme would be making a mistake about the true enjoyment found in walking long-distance: it isn't necessarily the things you see along the way, but how they link up with a sense of achievement. That's what can make a walk though incredibly banal space feel exciting. It’s about progressing more than anything else.

As I tried to ruthlessly qualify along these lines the

meagre distance I’d covered in the first few miles, I thought about how the

path to the east of Ipswich was much better kept than the one I travelled a

summer or two (or three or four) before. I used to traipse up the River Gipping

to Stowmarket: blocked by marshes without warning I would wade through reed

beds and silted fords alike. “This is a cakewalk by comparison”, I said to

myself, out loud, no-one nearby, a good time for that stream of consciousness

stuff. I realised too late that I had the wrong idea: sight-lines of an

electric fence followed up by a series of close-knit nettles. I didn’t much

want to give myself an electric shock, on the fringe of a cattle field, given a

wanton guess that the electric shock to be withstood by a cow would be much greater

than my own tetchy tolerance.

I was mulling then, barely within the fringes of the

egotistic, on my own weakness. Mulling whether there was any relevance to the

fact that I'd by-and-large spent previous summers on unforeseen primers for

this same walk. Wandering around Suffolk, by foot or by bike, without really

getting anything else done. I followed the occasional "side hustle",

as us millennials have it, but walking was my full-time occupation. I

wanted the world to give me confidence that I wasn't the only one rambling. I

wanted to to allay my sense that I was the last novice in psychogeography, that

little literary discipline where the place starts telling a story beyond its own borders. As I rounded the path around tidy, tight-knit Tuddenham, the nettles

and the electric fence would jostle for competition, trying to take the footpath

by force. In the hopes of an apology for these nettles and fences and long-gone

beds of reeds, I wished for a conciliatory sign, maybe "we hope this

doesn't inconvenience your walk today". I wanted platitudes, the kinds you

got in the city, even in Ipswich. But platitudes on signs would give the powers

that be an excuse to stop tidying the world up, especially so far from where the

people were. The few that lived in the fields beyond Ipswich would suffer advice

notes instead of actions, plasters obscuring places.

I wondered whether a walk this long could tend itself

towards ideas of a higher station. It did for Sebald, reaching into the East

and dreaming. I aimed to stew my thoughts like Sebald, but resorted to

giving myself overdue grief, wondering if my writing was just an excuse for a penchant for

overthinking. Due right of the path, I paused and noticed an abandoned farmstead. It was a

building that couldn't be differentiated from any other of its type: matching

every one I'd seen, from the Pennines to the Catskills and beyond. It was the

shared architecture of destitution, subconsciously drummed into us because of

some incredible human (yet inhumane) fear of poverty. Internalised

architectural contempt. Dead wood. Definitely overthinking.

But I felt like I was doing a good job of weaving together, however incoherently, all the things I witnessed along the journey. False confidence in this sense made me wonder whether throwing ourselves off social media could help turn people back into natural storytellers. The promise inherent in the midst of a journey affords depth to things that would seem obvious if they were dreamed up in the midst of an armchair. We take musings for granted when we have better things to be doing than muse. Randomised asides can only feel innovative when they’re dreamed up off the beaten track, with a story behind the light bulb moment and enough pause to recognise the bulb as it flickers.

The footpath between Playford (a village green and its thankless suburbs) and the town of Woodbridge was only a hillside behind the train line - which I could always hear trundling by, but could never seem to catch with my eyes. When you ride a train through a space you know, you can never quite see the countryside you recognise from the car window or the hazy hand-over-the-eyes. Cuttings and embankments and viaducts and tree lines and the speed, the sheer straight line speed, all conspired to make the view of the world differ.

At the edges of Ipswich, things are rough, peaks and troughs

of development hidden behind over-egged hedgerows. The concept of a particular

place, “Martlesham”, was a divided territory. There was Martlesham Heath on the

one hand, a vast industrial complex on Ipswich’s eastern fringe, and Martlesham

Village on the other, this charming rural hideaway of dispersed houses,

warehouses, farmhouses, and miniaturised marina, all completely out of sight

from the confluence of the A12 and A14 roads. Roads were just letters and

numbers, maybe maps, but nothing if not unseen until up close. The ribbon

development was so clear cut that you could come off the wrong side of one of

those roads and suddenly feel like you were in the middle of nowhere.

In the middle of that middle of nowhere I remember

remembering something. A turn of phrase:

"The demijohn exploded and all of the wall was

covered with cockroaches..."

I’ve looked the words up since and I don’t know what they’re from. A quote from something? I’m concerned it was something a friend told me. Better than a friend. But I know for a fact her demijohn never exploded. So whose did? And why did this phrase gel so perfectly, given I’d been thinking of her activist background only hours before, staring down propaganda in opposition to a bypass that has yet to grace these too-often fallow fields? #stopthebypass. Simple stuff. You could call it cliché, or you could call it memorable. Blurring binaries, just like the bypass would blur town and country, drawing out Ipswich’s edges like vectors in a design studio. Clay and soil no longer played their bit parts in the theatre of planning permissions. Campaign Against // The Northern Bypass. Those poor slashes, an accidental parody of activist culture, kitschy caricature. Cockroaches feeding off the leaking demijohn. The country folk can’t decide which of the three proposed bypass routes they hate most. Our world is on fire, and in the provinces they are arguing about byways of bypasses, placards by-the-by, only seen on sleepy Thursdays by the fool out walking. Me. I loved her and her bleeding demijohns.

On the way to the burial ground at Sutton Hoo, I wondered if

you could use blackberries to measure a journey: the different flavours of each

variety of each fruit shaped by the acidity of the soil, the rain and the sun,

the way the wind blows. Changing the intensity, the sourness, the bitterness,

all corners of the flavour from place to place. So I totted things up as I went

along. While I could gauge the difference between the twenty-odd unwashed

berries I consumed along the way, it was at Rendlesham Forest when I took a

moment; the berry tasted of chemicals. Something in the water? In the

forest, before the trees crowd out the sky? The forest was false, thorny

heath: promises of leafy biodiversity ratcheted year on year by the airfield

just beyond. Stirring crickets and, apparently, adders. 28 miles. I didn't

catch a single snake, but I caught more than one bout of mild, maudlin

trauma. I think to myself (not necessarily because there are no snakes)

that “this is rather perfect” - and suddenly an anecdotal stream of memories

flies into my head again. A turn of phrase I associated, purely incidentally,

with so many things: tumbling into a poorly lit room at one in the morning, a

drip of the third pint on her bobbled jumper, talking around things for hours.

I felt brilliant in the head back then.

Years later, in the government office, I would notice a

poster that for me paid testament to the mediocrity of my own profession. “If

it’s got a name, it’s not a discovery”. Some middle-management-depressant

interpretation of project work with a touch of Da Vinci-y dismissal. Well, I want to name my

discovery now, and, against the grain of “adulting”, I want to tinge it with the

adolescent brush. I want to call it angst-xiety: resentment and

anguish all in one.

The cockroaches fled the demijohn. She filled it with cider,

usually. She filled me with angst-xiety. We don’t talk; there’s some

nondescript barrier, built by past people who were only retrospectively

foolish. I rationalised, pretended it had been thrown up by the ubiquitous

unkindness of contemporary discourse. Really, I threw it up myself, or perhaps

she did and I was complicit and simply let the photos tear and the

conversations clear. An “eye rhyme” there, clear and tear, two phrases that rhyme in spelling

only. In our heads, lost in thought, do we rhyme by spelling or by speech? Logic

would lean towards speech, but metaphor might suggest otherwise... To “record”,

in the age of machines, is multimodal; machines “write to disk” and “read” files.

Listening implies less process. In the 28 mile moment I was too

emotive to think of writing. Audio notes were my device’s gift, to be able to

“record” when I couldn’t, breezing through forest furze and ignoring the

burning arches in my soles.

Some of the reed beds towards Orford look purple or even

lilac on the maps. By the 24th mile I am completely at odds

with the interest offered by the more peculiar corners of Suffolk; an artists’

studio beyond bleached watermills; a country house-come-holiday home with

families-come-cricketers in the garden. I could join in. Vouchsafe with an

onion. But I don’t; I feel like I’m fleeing from opportunity as it finally

starts to open up to me. The walk is a flower in late summer, some lily you forget

to water, only promising when you think of how things will end.

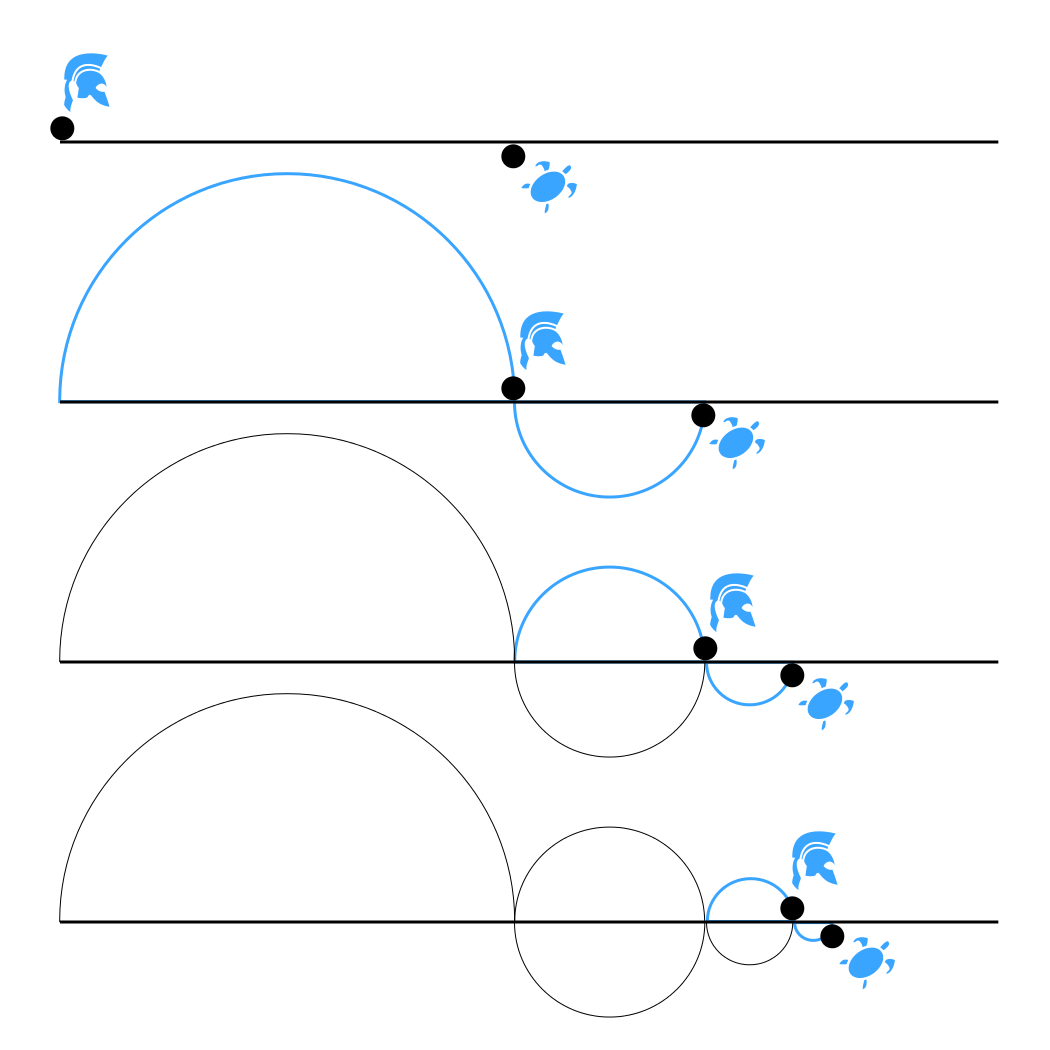

I adored Zeno’s paradoxes; Achilles and the Tortoise in

particular:

“In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started, so that the slower must always hold a lead”.

Aristotle, Physics, VI:9

Smaller and smaller steps failing to change the outcome. The tortoise always looks like it is beating Achilles. It always feels like there is a little longer to walk. As with any journey, the last mile is the hardest.

I pointed at the village sign in Orford and held my phone camera in my other hand, turning what might otherwise be charming and irreverent in my eyes (I had the casting vote here: no one else was watching) into an act of social media self-gratification. Limping into town, having visited before in anticipation of a riverside walk or a country market, I resented the pavements and looked to back-country padded grass with nostalgia. I had walked 28 miles in boots that were decisively not made for walking, and all I had to show for it was a delicious onion. I only discovered the onion was delicious after the fact, incidentally – although the smell stays with me a summer on. Earthy, rich, fresh from tilled soil. A place removed, a token taken from country to town. I am personifying an onion, no, I have to, all my other memories of the journey were flimsy words, inevitably two-dimensional. Spoken, now read. Recorded both ways. Until the journey was recorded like this, I felt like Achilles chasing the tortoise. Always a little longer. Another layer within the onion. Enough with the anecdotal, up with the permanent; I want to close the paradox of this journey. I want to cork up the demijohn. I want to forget the onion’s scent. And I want to walk again.

Comments

Post a Comment